I lived in an apartment once that flooded the night I moved in. I counted myself lucky I had already moved electronics into a different room than the one where the water was pouring in, but stepping into a puddle in my socks in the dark was no less a shock. The rest of the night was a panic of lifting everything out of the spill area and moving it, dripping, onto towels in the other room. I was terrified by what it would do to the floor; I was saved by a partner whose father owned a water vacuum. And then when I tried to finally go to bed, around 4 AM, my downstairs neighbor screamed up the stairs for me. The flooding had seeped down the walls of his apartment, damaging his cabinets and sending him into a similar spiral as I had just been through.

*

*

A bare-chested man (Father) pours water over the head of a young woman (Mother) whose hair is hanging down over her face into a full washbasin. As she stands, shaking her hair out lightly, we see how weighted down it is with water. We keep expecting her to throw it back, but she remains masked by this curtain of drenched hair even as she stands fully erect in the center of the room. The camera pulls back – the basin is gone, her hair is dripping onto the floor. The walls of the room, we can see now, are mottled with damage. Uneven textures, long set-in remnants of rain and wet rot striate the interiors. Drywall, but not so much. The ruin of the room frames the woman at its center, and still we cannot see her face.

Suddenly the empty room (she is standing there no longer) is falling apart, water pouring in from the ceiling which is rapidly losing large pieces to sogginess and gravity. They fall down into the room and crash to the floor, which is now covered in a great puddle. The shards of ceiling send spray from the pool splashing as they descend in slow motion. The woman is walking through the deluge, her hair finally back from her face. As she looks up, she briefly looks into the camera – looks at us – before turning to observe herself in a mirror which has streams of water running down its face. It is not as if she does not feel the rain, but as if she, unlike us, expected it.

The camera pans away from her, across the now slick textures of the cratered walls, until it once again lands on her, wrapping a knitted shawl around herself and looking at something we cannot see. The camera swings until it is almost matching her eyeline, and then cuts to her reflection in what looks like the glass over a painting hung on the wall of the room. Except this is not the young woman we have seen so far; it is herself, but much older, her skin marked by years as the walls are by the water. She reaches out and wipes clean the glass so she can see herself better.

This sequence from “Mirror” isn’t the first instance of a scene like this in a movie by Andrei Tarkovsky – far from – but it is, for me, the one most piercing. It is something about the slow quiet of the action, the steadiness of the woman’s bearing, and then the silent shock of the rain falling in through the ceiling. Perhaps it’s the slow-motion coupled with the high-contrast black-and-white, emphasizing the oneiric quality of the sequence. And indeed, that’s what rain inside, recurrent in Tarkovsky, always feels to be: dreamlike. An element where it is not supposed to be.

*

Rain does not fall cleanly in Tarkovsky. It is not the kind of dream in which it snows indoors but does not stick. The rich wood grain of the floor becomes slick with water, pooling regardless of expensive furnishing the way real rain does. The faces of the figures drip while their hair is plastered against their foreheads. It will ruin the books. It will ruin the upholstery. It will ruin.

It’s important that the rain gets on you. Rain falls in too many American noir films with the hero safely dry behind venetian blinds, so dry that he can let a cigarette burn. If the rain were to stick to, soak through the heavy fabric of his suit jacket or trench coat, he would be forced to interact with it bodily. He would experience its effects. He would be subject to it. And the masculine hero cannot tolerate to be acted-upon in such a way; it is he only who is supposed to act.

Film and video is a field perhaps uniquely subject to the diktats of water. I once spent weeks preparing for live TV coverage of a parade, and in the final forty-eight hours before it began had to prepare to call the entire thing off in case it began raining on the day of the event, as it had been threatening to do. Better-funded studios than the one I was working at have better ways of continuing their work in the rain, but options like those weren’t available to us. Months beforehand, in fact, almost all operations had to be suspended for the day when a pipe began leaking into the room where all of the servers that kept the studio running were housed. If the water had harmed them, that would’ve been the entire operation out the window. Sunk cost, as the saying goes; unusually apt in this instance. Water interrupts the efficiencies of these technologies, poking a hole (or perhaps slowly, slowly wearing away at, in the extended seepage-time of the universal solvent) in their narratives of mastery.

*

*

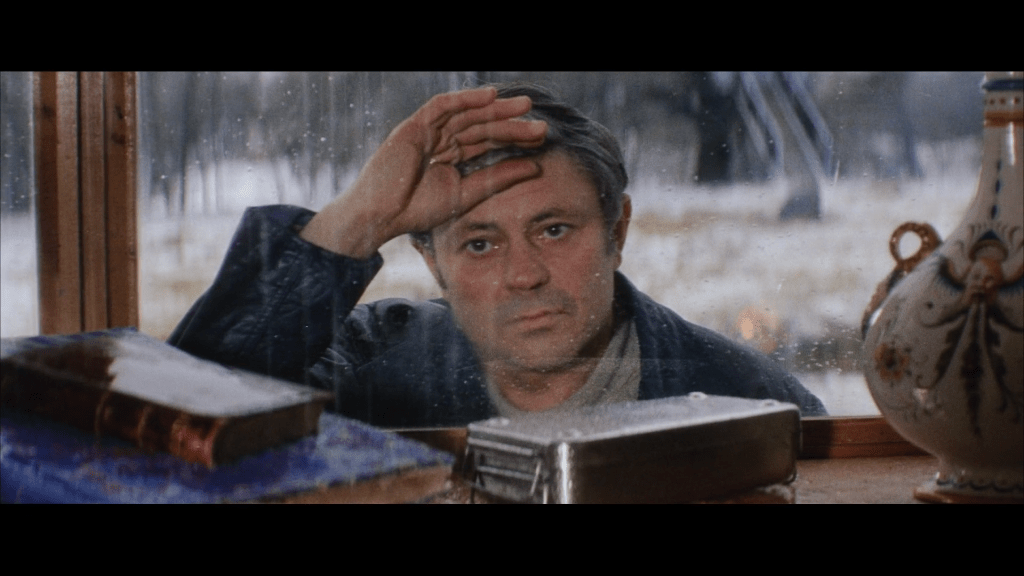

The fact that something is terribly off is first indicated by the water falling onto the stacks of open books. The old man (Father) has his back turned, his sheepskin vest facing us, and at first it seems that perhaps he hasn’t noticed the calamity occurring behind him as the pages are soaked through. But then water falls on him, also, standing in the supposed safety of his indoor study, and as he fails to react he betrays a more fearful wrongness than it at first seemed. His son, the film’s hero, looks in the window, and his expression becomes one of pained acceptance as he comes to realize what is just starting to dawn upon us in the audience, what the final shot of the movie will soon make clear to us. This is the same house that the first half hour or so of the film was spent at; a space of relative coziness compared to the psychodrama of the space station that made up its longer main section.

But something has been “off” for much of this film, including the portion taking place on the space station. At the surface level of plot, this space station orbits the ocean-planet Solaris, which is possessed of a sentience that attempts to communicate with the scientists onboard by reaching into their unconscious minds and making into flesh and blood figures from their memories or fantasies. But this plot is conveyed primarily in one presence and many absences. The presence is the deceased wife of the main character, scientist Kris Kelvin, who is born anew (and anew and anew) by the power of Solaris; but what interests me in this context is the absences.

Rewatching “Solaris,” it struck me how terribly polite Kelvin is in the face of the strange behavior exhibited by the scientists who have been living aboard the space station – and how uncomfortably familiar that politeness felt. When Kelvin arrives aboard the station, the first scientist he meets seems surprisingly unsurprised to see him; his reaction is glazed over and toneless. Kelvin’s response is studiedly polite. When Kelvin attempts to speak to the second scientist aboard and he won’t allow him in the room he’s inhabiting, only speaking to him through the door and keeping it as close to shut as he can when finally forced to leave, Kelvin is again studiedly polite. Even later in the film, after Kelvin has been aboard the station for an unclear but lengthy period of time, he and what remains of the crew throw a party for one of the scientists onboard in the station’s comparatively opulent library, and sit around silently until they decide that “the guest of honor” won’t be making an appearance. And, of course, at that moment he does walk in: his gait unsteady, the shoulder of his suit jacket torn open, and his demeanor somnambulist.

“Oh,” he says, “everyone’s already here.”

“You’re an hour and a half late,” the other scientist replies nonchalantly, as Kelvin simply sits there like this is all expected and natural.

It is the kind of politeness one has prepared for those not able to really take in the reactions of others. It is, in my experience, not dissimilar to the politeness that the family or friends of somebody with a substance use disorder learns expertly to execute. And it is a politeness that marks, in its very refusal to perform it outwardly, a break with a past version of the loved one in question to which one fears there is no return.

This reading colored my reaction to the final scene, in which Kelvin returns to the house where his father lives only to find it in a state of escalating watery decomposition. It is, the rain soaking through the ceiling seemed to indicate, impossible to return to the comfort of that house after experiencing Solaris. Contact with the ocean-planet, with the slipperiness and antagonism of one’s own memory and unconscious and the interpenetration of boundaries between it and the other, is a limit-experience past which whatever antebellum homespace one may wish to go back to is not only no longer extant, but is itself swallowed up in the deluge of that disruption. Upon trying to do so, and perhaps upon realizing how fruitless his attempted return is, Kelvin falls to his knees before his father. The camera pulls further and further back until we see that the home is in fact not the home he had been living in at the start of the film, but is an island in the vast ocean-planet – that it is perhaps just another memory given shape by Solaris which is already falling apart.

*

Mark Bould’s The Anthropocene Unconscious dedicates a chapter to art which depicts, or gestures to, or could be read as thinking through, floods. These floods (must) presage the flooding that climate change promises to bring to large portions of the world in the coming years, even if that is supposedly not what they are addressing in their fictitious contexts. After discussing fantasies of deluge in works by Karl Ove Knausgard, he glosses a scene in Arundhati Roy’s novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness in which the security guard Gulabiya falls asleep at his post and dreams of a world in which the village that he grew up in hadn’t been flooded to build a reservoir.

He dreams simultaneously of a world lost and a world restored, of upheaval and of fullness. Of the present over-laid by the past it negated, which in turn negates an unbearable present. Of his village from the bottom of the lake, where the air has become water and swimming, flight.

He dreams an absurdity: the actually existing one.He dreams slow violence. The unspectacular time of dispossession and dispersal. Of irrevocable environmental change engineered by dams and development, by the global economic system of which they are both parts and epiphenomena. And of circumfluent fossil fuels: diesel above, diesel below; not a divine promise but an iridescent threat.

Mark Bould, The Anthropocene Uncionscious

In these images of elements transposed, of displacement and disaster, natation and navigation, flood and flight, Knausgaard and Roy mash up modernity with its consequences. Superimposing submergence and salvage onto everyday life, they not only make externalities visible but show them to be internal, intrinsic. Haunted by myths and memories of deluge, by anxiety and anticipation, they glimpse worlds – possible, impossible, actual, alternative – that ghost each other. That flicker in and out of view, intertwine and blur.

In Bould’s reading, the flood in these texts are inextricable from the technologies which enable them, technologies developed in and for the creation and reproduction of capitalist modernity. These technologies, this history, is part of the unconscious of the texts, unstated but constitutive. The recrudescence they present of biblical flood myths – a tenor that would no doubt be more palatable to Tarkovsky – is unthinkable in their contemporary context without these technologies hanging shade-like in the mental background.

And indeed those technologies themselves are not only instrumental in directing water in the short term (and perhaps in fostering the illusion that it could be so easily directed forever), but for creating the conditions for the far less controllable flooding in the long term that climate catastrophe promises. Already, millions of people living in densely populated and climate-vulnerable nations like Bangladesh are being displaced – if not killed outright – by flooding whose regularity and intensity is being exacerbated by climate change. Estimates are currently that “flood displacement… is likely to double by the end of the 21st century even under the most optimistic combination of scenarios.” And to address these crises is to address, whether consciously or in the unconscious framework of the question itself, the fruits of a colonial regime of extractive capitalism. In a pre-flood era such as ours, to think of the waterlogged is to imagine the future history of social totality.

… for ever since they have existed, the bourgeois class has been waiting for the Biblical flood.

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia

*

*

Science fiction itself may be thought of as the unconscious of “Stalker,” Tarkovsky’s second entry in the genre following “Solaris.” The second film has none of the first’s futurist art design or explicitly space-age setting, and besides its whistly electronic score, there is little in the text of the film that is particularly unrealist. Even the powers of the wish-granting room at the supposed center of the narrative are never actually tested; for all we as viewers know, they may be as much a fantasy in the world of the film as they are in our own. But the generic conventions of a science fiction adventure still structure our experience of the film as an audience, both in the areas where it fulfills them and in the far more common areas where it defies them and may even leave us frustrated.

An oversimplification for the sake of brevity: “Stalker” is a movie about two bourgeois men being led through an area marked by the destructive capacities of water by a prole who understands it better than they do. These two men – a Writer and a Professor, both comparatively well-heeled and referred to only by those titles – have hired the nervous, shabby Stalker of the film’s title to lead them through a mysterious area known as The Zone, which we are informed by titles at the beginning of the film was the site of an ill-defined and potentially extraterrestrial visitation and has been cordoned off by the military to prevent entry. We later learn that there is a Room inside the Zone which can grant the deepest desire of whoever enters it. Or so the story goes.

Like the names of the other two main characters in the film, “Stalker” is a job title: Stalkers, in the world of the film, are professional guides through the treacherous and ever-shifting landscape of The Zone to reach The Room.

The Zone is a theater of desolation. Bodies, buildings and infrastructure are all decaying around the protagonists in equal measure as verdantly forbidding plant life reclaims the territory they tramp through. And the closer they get to The Room at its center, the more waterlogged their environs become. In the middle of the film, after making their way through a crumbling tunnel full of onrushing water, hanging onto a threadbare rope to pull themselves through the rapids, Stalker and Writer come upon Professor, whom they had thought lost forever when he had abandoned the party earlier. The Zone, it seems, has lead them back to their companion. Stalker is so overcome by this that, without any group discussion, he decides that they will rest before continuing any further. He proceeds to lie face-down on the marshy ground as Writer and Professor, also finding places to lie among the damp moss and water-streaked concrete that surrounds them, begin arguing with one another.

They argue about science, art, human nature and their own motivations for entering The Zone as they begin to drift into sleep. Towards the end of the film, Stalker will refer to these men as ones who are forever “… thinking about how not to sell themselves cheap, how to get paid for every breath they take.” Their pettiness is on full display here, despite the high-minded subjects they poke each other about. Eventually, after they all seem to have fallen asleep, a nearly silent stream of shots showing the Zone suspiring around them is interrupted by a whispering voiceover:

And, lo, there was a great earthquake; And the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood; And the stars of the heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casts its unripe figs when it is shaken by a mighty wind. And the heavens departed as a scroll; and every mountain and island was moved out of its place. And the kings of the earth and the great men and the rich men and the generals and the mighty men and all free men hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains; And they said to the mountains and rocks “Fall on us and hide us from the face of him that sits on the throne and from the wrath of the lamb. For the great day of wrath has come, and who shall be able to stand?”

Revelation 6:12 – 17

A shot like this has happened before in “Stalker” and will happen again several times more: as the voice whispers on, the camera pans away from Stalker’s sleeping face over the polluted waters that surround him, and we survey the submerged detritus littering them. Snails, syringes, the torn pages of books drifting slowly apart, cracked bottles and chalices, rusted metal coils, coins, tin cases, fish swimming over rotted cables, Christian icons, submachine guns, algae floating over all and, underneath much of it, cracked and peeling floor tiles: so this, too, is a flooded interior.

Famously, a nuclear power plant looms over a later scene in “Stalker,” seen by many as a foreshadowing of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, still seven years in the future at the time of the film’s release. Whether or not one reads it as prognostication, it is of a piece with the aesthetic environment in which the rest of the film takes place. The entirety of the story, particularly inside The Zone but outside of it as well, occurs in the shadow of the disaster of industrial modernity, in the hollowed-out bodies of factories and warehouses, through the arteries of rusted railway lines and sewer pipes. In juxtaposition to the overwhelming power of these spaces, the argument between Writer and Professor before falling asleep takes on a truly pathetic quality. They are trying to one-up each other in the hierarchy of a world that has already ended, and this is so clearly evidenced by the submergence that surrounds them even as they continue to squabble. Much like our own, the world of “Stalker” is one simultaneously pre-, post- and parallel to a developmentalist apocalypse.

*

When in the beginning Elohim created heaven and earth, the earth was tohu va bohu, darkness was upon the face of tehom, and the ruach elohim vibrating upon the face of the waters…

Catherine Keller’s Face of the Deep comprises an extended meditation on, and explosive exegesis of, these words from Genesis 1:2 and their implications for theology. In her rigorously argued and far-reaching reading (which is no less enjoyable to read for the density and power of its scholarship), these words at the very beginning of the Hebrew Bible give the lie to the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo which was developed in the early centuries of Christian theology and came to dominate the thinking of the established church. According to Keller, creatio ex nihilo (Latin for “creation from nothing”), the doctrine that God summoned existence into being from naught or from capital-H Himself only, not only conflicts directly with the tehom of the text as written, but is a case of motivated misreading that serves very particular set of authoritarian sociopolitical aims.

Keller writes that “Any theo-politics of omnipotence, left or right, will gravitate towards a theology of machismo – which lays itself open (indeed exposes itself) to gender analysis.” She reads into those early works that papered over the scriptural pre-existent waters with a theory of creation from nothing not only machismo, but indeed an explicit repudiation of the feminine-coded; of the “chaotic,” of the not-entirely-self-sufficient, i.e. of the relational. The instinct behind this is one which she analogizes to the slaying by Marduk of his mother, the sea-goddess figure Tiamat, in the Babylonian creation epic Enuma Eilish. At the same time, she acknowledges that one of the afterlives of this watery mother figure is in the language of the very text she is herself enumerating:

The face of the deep was first – as far as we can remember – a woman’s… Tiamat migrates into Hebrew as tehom. Moreover, Genesis 1.2, while ascribing no personality to the deep, does use the feminine noun tehom as though it is a proper name. “The tehom signifies here the primeval waters which were also uncreated. Significantly, the word always appears without an article in the singular and is feminine in gender.

Catherine Keller, The Face of the Deep, Quoting from Brevard S. Childs, “Myth and Reality in the Old Testament”

It is in opposition to the erasure of this originary deep that Keller lodges her critique. This erasure has a reach so broad -the establishment of a creation from nothing being the starting point for thousands of years and pages worth of thought – that in opposing its logical starting point, Face of the Deep places itself in a position, and a (counter)tradition, of radical dissent. In a section quoting from the work of Brazilian liberation theologian Vitor Westhelle, Keller writes:

[The ex nihilo] doctrine has provided the foundation of Western Conservatism. Western theologies of creation ground themselves upon “the order of creation.” Of the Eurocentric “sacralization of order” Westhelle writes: “Creation language has been permeated by language that stresses order.” … order is “most often an ideological disguise for domination, repression and persecution.” For “where order is the result of the demiurgic work of the ‘invisible hand’ of capitalism, where order is the patriarchal hierarchy, the stability and control of the whole society is guaranteed.”

Keller, ibid, Quoting from Vitor Westhelle, “Creation Motifs in the Search for a Vital Space: A Latin American Perspective.”

Keller proposes, in counter to these matricidal/patriarchal hermeneutics, what she terms a “tehomic theology.” This is a theology which not only acknowledges the watery chaos on which ruach elohim vibrated, but which understands precisely the things which the elision of that depth seeks to erase – relationality, unknowability, even a certain playfulness – as being the basis on which and from which creation itself is formed. This is an ethic which extends as much to the form of her argument, the stuff of which it makes itself, as it does the content;

The proposed tehomism necessarily implicates us anew in “the tradition,” that is, in the iteration of texts in which “she” left hardly a trace. But if “she is left with a void, a lack of all representation,” as the “nothing, the no/thing” of a lacking phallus, this does not mean she ever disappeared. If tehom turned into the nothingness of the Christian tradition, this does not mean that the sign matrix of the originary chaos evaporated. We seek out those she/sea traces among massively male texts not to reassure ourselves that Christianity was or is really OK for women. But whatever beauty and justice we may now articulate – we who read as and with women – will not flow from a new supersession, a new ex nihilo.

Keller, ibid.

It is not only in the dedication to the watery and the chaotic that I see a similarity to my desire to explore the scenes from Tarkovsky movies that I’ve written about so far, but in this aim to read actively and regeneratively the text at hand in its relationships, both conscious and un-.

*

My preoccupation with these watery moments in Tarkovsky is clearly born at least in part of their aesthetics of decay and disorder. There is a sublimity to the spectacle of ruin, of not only accepting decline but wanting to see what things will look like after it has happened. Water pouring in through the ceiling of my home would be (has been) a disaster; I am therefore fascinated by the image of it. Scale that up several orders of magnitude, and we have the appeal of disaster movies in general.

To suggest that Tarkovsky’s moments of watery interpenetration can be read through the prism of global capitalist decline is to skirt the complicated questions not only of the Soviet Union’s position within global capitalism at the time of these films’ productions, but of Tarkovsky’s position within the Soviet Union itself; questions beyond the remit of a piece like this one. But in each of the above scenes, the suggestion is of a place or time or system or people coming apart in the face of something greater than itself, difficult to grasp, and which underlies their very existence. Whether it is a child’s memory of home or the anticipated post-collapse future, the spectacle of water pouring in uncontrollably is the spectacle of eventual, and perhaps inevitable, destruction.

And yet: Keller’s theorizing of tehom is not of chaos and disorder as symptoms of decline, but of chaos and disorder as the necessary preconditions for creation itself, not to be avoided but to be embraced. This, I believe, is the other side of my fascination with these images: It is only from this ruin that a true newness can be born. Memories are soaked through and unreliable, the comforts we are socialized to desire are swallowed up in the ocean of their consequences, but the possibility of something else remains unforeclosed, even if the pathway there must pass through baleful environs.

I am resolutely opposed to assigning this feeling a polarity. It is neither positive nor negative, hopeful nor pessimistic; or at least, it is neither of these things entirely, but all of them at once. There is true terror here, but terror is also part of the classical romantic sublime. As in most things, there are irreconcilable differences coexisting within a sensation both singular and multiple, and one of those valences is a desire for something other than all this shit in which we live. That is a desire whose unconscious is the end of what is. Not a return to tohu va bohu, not even the creation of a new tehom, but a scattering of these elements that they may configure themselves into something novel whose potentiality was/is always there, though not necessarily or essentially. In other words, what hope there is present in these images of watery ruin – which must live side-by-side with the pain of seeing the destruction of the familiar – is hope along the timeline of biodegradation and reconstitution. This is a timeline that necessarily does not include myself, but one which I hope includes some future humanity.

Leave a comment